Updated from an earlier post. On September 5, 2013, in a professional negligence case against two Colorado appraisers by the FDIC, a federal court ruled on an issue concerning USPAP confidentiality. It was a simple issue, but it’s one of the very few court decisions relating to USPAP’s poorly written confidentiality rule (this previous post here explains why the rule is poorly written). This is the rule:

An appraiser must not disclose: (1) confidential information; or (2) assignment results to anyone other than: the client; persons specifically authorized by the client; state appraiser regulatory agencies; third parties as may be authorized by due process of law; or a duly authorized professional peer review committee …

The question for the court was: in response to a discovery demand in the case, did one of the defendant appraisers have to handover appraisals of the same property that were for different clients and unrelated to the loan at issue despite the confidentiality rule in USPAP? The court’s answer was an easy “yes.”

The FDIC Lawsuit. The FDIC’s negligence claims in the lawsuit stem from two appraisals of a single family residence in Grand Junction, Colorado. The FDIC filed the case as the receiver for failed lender Amtrust Bank.

The FDIC Lawsuit. The FDIC’s negligence claims in the lawsuit stem from two appraisals of a single family residence in Grand Junction, Colorado. The FDIC filed the case as the receiver for failed lender Amtrust Bank.

The following facts are alleged by the FDIC in its complaint: In January 2008, defendant appraiser Broom prepared an appraisal of the home for a proposed cash-out refinance being arranged by Clarion Mortgage and funded by Amtrust. He appraised the property for $1,900,000. The underwriting rules for a large-cash out loan required that Clarion obtain two appraisals and, thus, according to the FDIC, Clarion obtained a second appraisal from defendant appraiser Pace. He also appraised the property for $1,900,000 according to the FDIC. The FDIC alleges that the “two appraisals were not independent valuations of the Property” and that both appraisers erred by overstating the square footage of the home by counting a “detached theater room as part of the main dwelling’s living area.” The FDIC alleges both appraisals misstated the “gross living area was 5,053 square feet, when it was actually 4,523 square feet.” What’s not clear from the FDIC’s vaguely written complaint is whether the second appraisal was a really a review that merely concurred with the first appraisal or whether it truly was an entirely separate non-review assignment. The FDIC has misleadingly pleaded other complaints with regard to this issue.

In its complaint, the FDIC alleges that, based on the two appraisals, Amtrust funded a $1,025,000 loan to the borrowers, who received $403,000 cash-out at closing. According to the FDIC, Amtrust would never have funded the loan at all if the property had been properly valued by the appraisers (the FDIC does not allege what the correct valuation should have been) and, thus, the appraisers are liable for “damages . . . in an amount to be proven at trial, plus interest, costs, and attorneys’ fees.” In other cases, the FDIC has contended that such damages should include: the entire unpaid loan balance, all accrued interest, all accrued late charges and all costs associated with foreclosure handling. (For appraisers, the FDIC’s lawsuit against the appraisers points to the importance of considering whether an E&O policy contains an exclusion for claims by the FDIC or similar regulatory agencies. That topic has been written about in several recent posts, including the post at this link.)

The Confidentiality Issue. The USPAP confidentiality issue arose when the FDIC demanded that appraiser Broom produce four prior and subsequent appraisals of the same property but for different clients than the failed bank. With respect to the confidentiality issue, the FDIC first pointed to the fact that there is no “appraiser privilege” that would prevent disclosure of confidential appraisal information in general and that the specific confidentiality rule in USPAP allows for disclosure when authorized by “due process of law.” The FDIC also pointed out that to the extent that confidentiality should be maintained (e.g., for the purpose of protecting private consumer information), that confidentiality would be preserved by the existing protective order in the case. This was the actual argument made by the FDIC in its brief:

In opposition, the defendant appraiser tried to argue that USPAP nevertheless did prohibit him from disclosing the other appraisals for other clients and that disclosure would also somehow prejudice the outside parties for whom the other appraisals were produced. The appraiser pointed to a 1974 (pre-USPAP) case U.S. v. 25.02 Acres of Land in which disclosure of appraisal work relating to nearby land by an appraisal expert witness in a condemnation case had been denied on the basis of prejudice to the other clients of the appraiser — the court believed production would have prejudiced the other landowners because of on-going condemnation litigation.

In the present situation involving appraiser Broom, however, the issue really wasn’t a hard question for the court to decide. The court ruled that USPAP did not preclude production of the appraisals and that there were no genuine concerns about prejudice (especially given the existence of a protective order in the case). This is what the court wrote:

The court’s ruling is consistent with how another federal court addressed the USPAP confidentiality issue in U.S. v. 2,091.712 Acres of Land, Case No. 4:09-CV-88-BO, E.D. North Carolina (2010). This is one of the very few other published decisions addressing USPAP’s confidentiality rule and was cited by the FDIC in its motion. Similar to the facts in the 1974 pre-USPAP case cited by defendant Broom, in 2,091.712 Acres, an expert witness appraiser in a condemnation case was subpoenaed to produce appraisals he had performed of properties similar to the subject property. The subpoenaed appraiser objected on the basis of USPAP’s confidentiality rule. Like the court in Colorado, the federal court observed that “[t]he law does not afford an evidentiary privilege to professional appraisers” and further “the USPAP rules themselves explicitly contemplate the production of such documents to ‘third parties as may be authorized by due process of law.’” That court, too, ordered that the appraisals be produced.

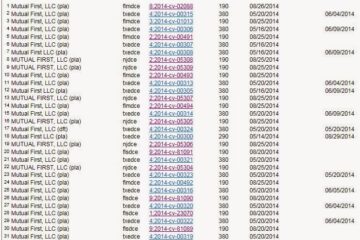

The following documents from the FDIC case discussed above are available here on www.appraiserlaw.com:

- FDIC Complaint, FDIC v. Broom, et al., 12-3-12.

- FDIC Motion to Compel, FDIC v. Broom, et al., 8-5-13.

- Order on Motion to Compel, FDIC v. Broom, et al., 9-5-13.

The defendant appraisers in this case and in other cases discussed on the Appraiser Law Blog are not insured by LIA Administrators & Insurance Services. We do not publicly discuss cases involving appraisers who have E&O insurance with LIA. All cases discussed on the Appraiser Law Blog are matters of public record.

Peter Christensen is an attorney who advises professionals and businesses about legal and regulatory issues concerning valuation and insurance. He also serves as general counsel to LIA Administrators & Insurance Services. He can be reached at [email protected].